In the 1980s, as Great Britain under Thatcher was undergoing tumultuous changes, something new was being born in Manchester. And this new thing was born from the city’s industrial heritage, in a former warehouse building on Whitworth Street West. It was there, in 1982, that “The Haçienda” club emerged, created by Factory Records and the band New Order. And this place was more than just a nightclub. More at manchesterski.com.

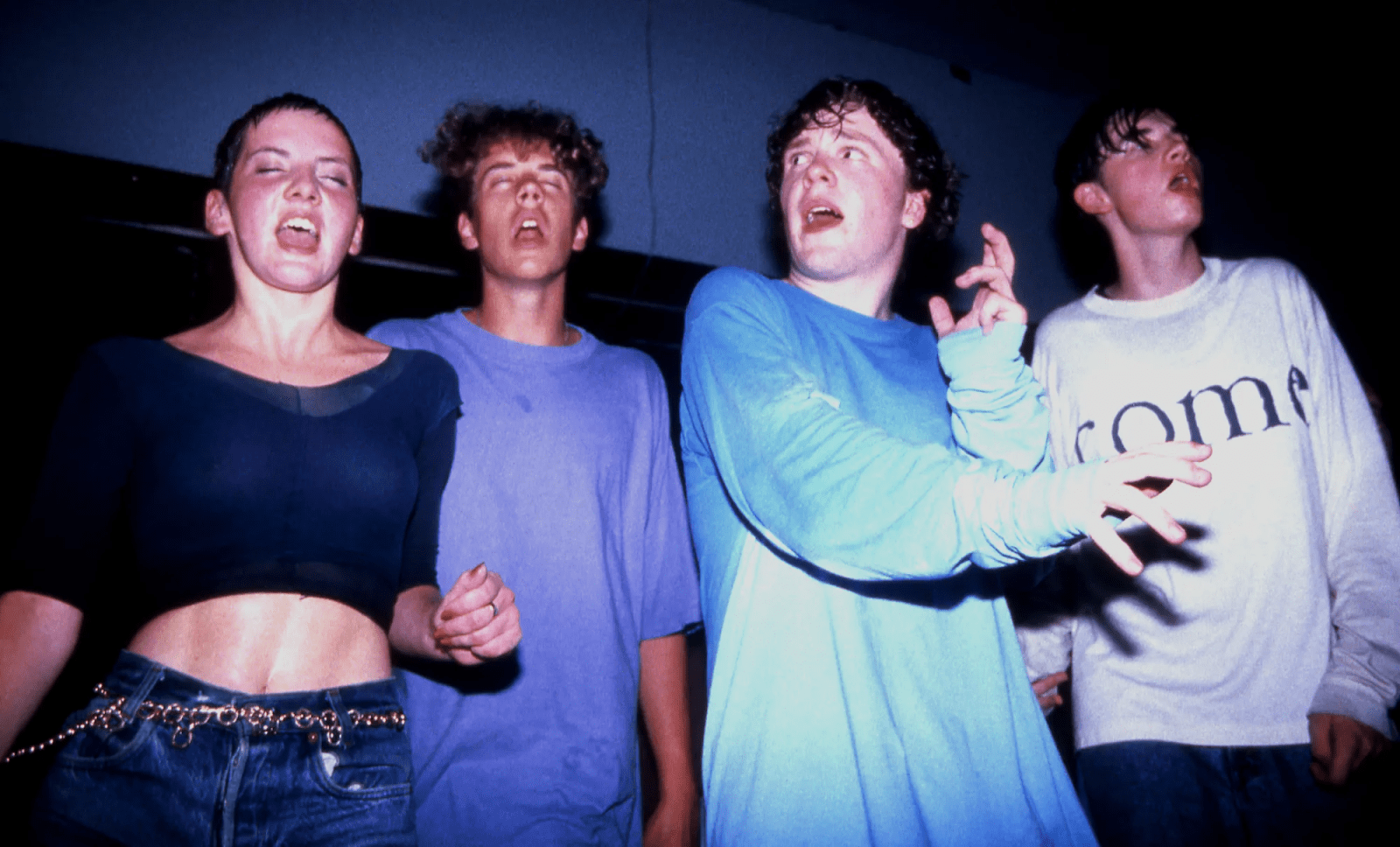

“The Haçienda” became a symbol of freedom. It was a space where post-punk met electronic music, where the dancefloor brought together working-class kids, students, artists, and simply those looking for a new rhythm of life. There was no snobbery here—just music, lights, dancing, and the feeling that you were on the threshold of something big.

The club’s design was revolutionary, as was the idea itself—to make Manchester the centre of the musical future, not a city of the industrial past. In an atmosphere of general gloom and decline, “The Haçienda” became a unique place where youth forged the future of British and world music.

This club changed everything: nightlife, culture, and the way Manchester sounded to the rest of the world.

How did it all begin?

“The Haçienda” club opened in the spring of 1982 and, from its very first days, became a venue for musicians, DJs, and fans of the alternative scene, both local and from other cities. The opening night is remembered for a performance by the comedian Bernard Manning, who famously misjudged the crowd’s mood and returned his fee.

That summer, the German band Liaisons Dangereuses performed, followed by The Smiths in 1983. One of the landmark events was Madonna’s first UK performance in the winter of 1984—she performed “Holiday” live on Channel 4.

“The Haçienda” quickly became a platform for live performances and musical experimentation. Acts like the Happy Mondays, The Stone Roses, Oasis, 808 State, The Chemical Brothers, and Sub Sub all played there. One concert by the band Einstürzende Neubauten even involved them using drills on the stage walls.

In 1986, the club was one of the first in the UK to start playing house music. It became increasingly popular. This era turned “The Haçienda” into a symbol of the 1980s music revolution.

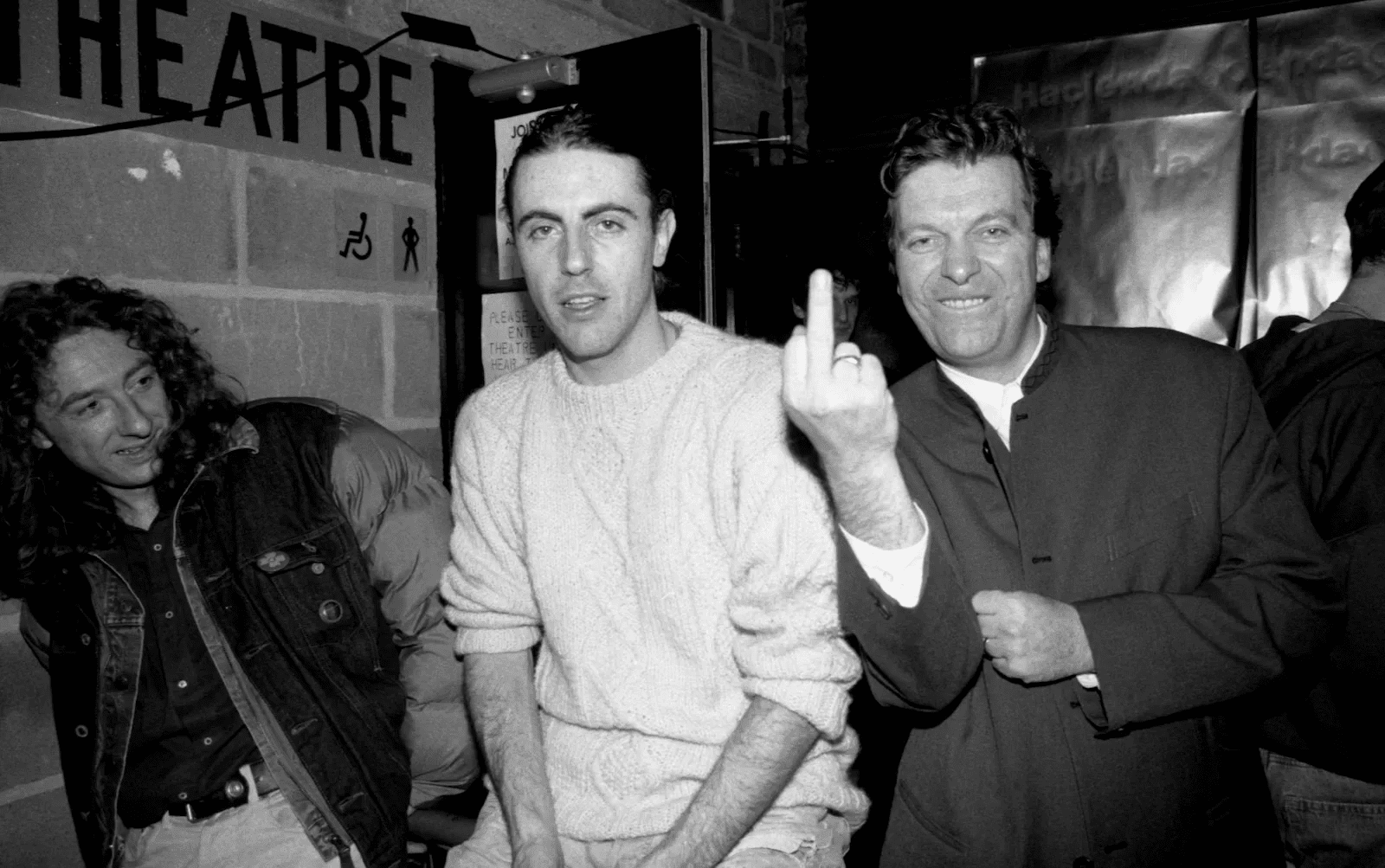

The location of “The Haçienda” is also worth mentioning. The club was located in a former warehouse at 11–13 Whitworth Street West, near the Rochdale Canal. Previously, the building was used for yacht construction and goods storage, but in 1982 it was converted into the iconic club. The project was initiated by Rob Gretton and financed by the Factory Records label, the band New Order, and producer Tony Wilson.

The iconic club included a stage, a dancefloor, bars, a café, a DJ booth, and a balcony. The basement housed “The Gay Traitor” cocktail bar—an ironic reference to the British spy Anthony Blunt. Other bars were named after his “colleagues”—”Kim Philby” and “Hicks”. Later, the basement became the “5th Man” music space, which hosted parties featuring famous DJs.

The sound and lighting were designed by Martin Disney Associates and Akwil Ltd. Everything was thought out down to the last detail to ensure the club’s atmosphere remained unique and unforgettable.

The Music Born on The Haçienda Stage: From Post-Punk to Rave

When “The Haçienda” first opened, nobody knew exactly what would come of it. But it was here, on Whitworth Street, that music which changed British and global culture was born: from post-punk and funk to electronic, house, and techno. “The Haçienda” was not just a music platform. It was the epicentre of a new sound, free from labels, rules, and clichés.

Post-Punk and Joy Division – The Club’s DNA

Back in the 1980s, the bleak, industrial, and emotionally resonant sound of post-punk was central to “The Haçienda”. But when Joy Division transformed into New Order, everything changed. It was New Order who set the musical trends in the club, blending guitar melancholy with electronic beats. In doing so, they laid the groundwork for the future of house and techno, which would very soon replace post-punk.

“Blue Monday” and the Birth of a New Kind of Dancefloor

The song “Blue Monday” (1983)—released by Factory Records and created by New Order—was a real breakthrough. It became the best-selling 12-inch single in history. It was played on repeat at “The Haçienda,” transforming into the club’s anthem.

This track had everything the club’s patrons loved: a relentless beat, synthesisers, detached vocals, and an elusive sadness that felt incredibly danceable.

Acid House Meets Manchester

In the mid-1980s, The Haçienda’s DJs began bringing over records with experimental house music from the US. At first, the audience didn’t know what to make of it. But with the arrival of Ecstasy, the rhythms started to be felt in a whole new way.

Thus, British acid house was born, and the club became its centre. It gained popularity not just in Manchester, but across the UK as a whole.

Madchester: Psychedelia, Rhythm, and Groove

By the late 1980s, a new generation of bands emerged. They had grown up on post-punk and house but added British humour, a casual attitude, and endless fun to the mix. These bands included the Happy Mondays, The Stone Roses, 808 State, and A Guy Called Gerald. Their songs were absurd and brilliant at the same time, and perfectly suited to the chaos of the club’s dancefloor. This mix of music, fashion, and drugs became known as the “Madchester” movement. And its heart, without a doubt, was beating in “The Haçienda”.

“The Haçienda” gave birth to countless global music trends. These included electronic music, the new culture of DJing, club residencies, the indie sound, and the formation of the British rave movement, which spread far beyond the city.

The “Death” of Manchester’s “The Haçienda” Club

Although “The Haçienda” was incredibly popular and a true cult venue that had its finger on the pulse of the era, in 1997, the club closed its doors for good.

By the mid-1990s, “The Haçienda” was no longer the club where the music revolution was being born. With its growing popularity came associated problems: crime, drugs, and street gangs.

The police regularly conducted raids, parties ended in fights, and the security staff feared for their own lives. On top of that, the club had never been financially successful. Most of the time, it operated at a loss. For Factory Records, it was a real financial black hole.

In 1997, after several crises and mounting pressure, “The Haçienda” finally closed its doors. The building was later demolished. A residential complex was built in its place.

It seemed that with the club’s closure, an entire era had ended. But “The Haçienda” was so legendary that it couldn’t just be forgotten. Its story lived on not in the building where the club once stood, but in the people.

For thousands, perhaps even millions, “The Haçienda” remained something much more than just a nightclub. It was an entire era. A symbol of how music can unite strangers, break down barriers, bridge class divides, and turn an ordinary evening in an industrial city into something magical.

“The Haçienda” became a metaphor for freedom. The freedom to create, to experiment, to find one’s own sound and one’s own place. And even decades after its closure, people continue to talk about the club—a British legend of the 1980s and 1990s.